Fixing the Rental Crisis in New Zealand

Part 1

Background.

There are approximately 600,000 rental properties in New Zealand, with the private sector providing the overwhelming majority, at around 510,000 or 85% of rental housing. The Government provides around 72,000 rental properties or 12 % of the total.

There are no precise figures on the size of the rental economy – but if we used turnover (in the form of rent) as a guide then it is worth somewhere in excess of $15 billion per annum.

While many believe that most residential rental properties are held by large-scale landlords, a 2015 NZPIF survey shows that 75.8% of residential landlords own just one rental property. Just 0.1% of all private landlords own 10 or more properties.

Tenants in State and Social housing are charged an Income Related Rent of 25% of their income. Kaianga Ora and Social Housing providers receiving a tax-payer funded Government ‘top-up' to market rental levels.

Renters in the private sector (not their landlord) receive an accommodation supplement which is considerably less the Income Related Rent government subsidy.

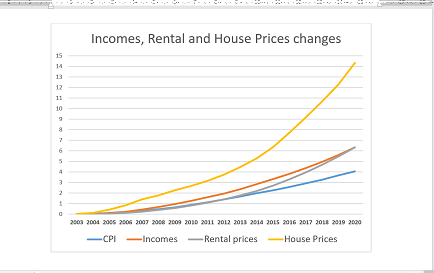

Rental prices over the long term have matched income changes. The following graph shows that over the last 17 years, rental prices have increased at the same rate as incomes.

This hasn't been uniform however. Incomes increased at a faster rate than rental prices from 2003 to 2014, however since then rental prices have increased faster than incomes.

The rental price increases are due to changes that have increased the cost and risk of providing rental properties.

Some of these changes, such as improving rental property standards, have provided better quality rental accommodation along with an increase in rental prices.

However other changes, such as removing building depreciation, ringfencing tax losses, introducing and extending the Bright Line Test plus removing mortgage interest tax deductibility have been implemented specifically to reduce private sector provision of rental property. While the stated reasoning for this was to help first home buyers, it has resulted in increased costs for tenants.

There are a number of challenges facing the rental property industry in New Zealand:

- Difficulty funding new rental properties (Banks criteria, Ringfencing of rental property losses)

- Disincentives to providing rental property (Bright Line Test, Tenants liability for damage, RTA amendments and removing mortgage interest as a tax deduction)

- Higher rental property taxes (Ten year Bright Line Test, Ringfencing tax losses and removing mortgage interest as a tax deduction)

- Increased compliance costs (Healthy Homes Standards. RTA Amendments)

- Higher costs to operate a rental property (insurance, rates, letting fees, repairs and maintenance)

- Difficulty in obtaining timely Tenancy Tribunal hearings to resolve problems

These challengers have led to a shortage of rental properties, higher rental prices than there should be, a shortage of emergency housing and a dramatic increase in the number of people seeking social housing.

NZPIF is focussing its strategies to fix the rental crisis on the real issues that are causing problems for the rental industry, including rental property providers, tenants and tax payers.

The NZPIF plan for fixing the rental crisis

Stable Homes

1. Workable long-term tenancies

Traditionally, New Zealand's rental market has been dominated by periodic tenancies rather than long term leases. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Renting if often seen as a temporary stop-gap step between leaving the parental home and buying your own house.

- Tenants usually rented at a time of their life when they were living a transient lifestyle and thus wished to retain the ability to move on at short notice.

- Landlords often bought an investment property while in their high-earning mid-life years potentially selling the investment when they retired or paying off the mortgage and supplementing retirement funds with the rental income.

- The majority of landlords are hands-on and self-managing, owning just one or two properties, and were reluctant to secede long-term control of their expensive investment.

- Before 90-day no stated reason notices were removed for all tenancies, they were not available for fixed term tenancies. This discouraged long term fixed tenancies as there is risk that the tenants behaviour could become problematic.

Recent moves in the New Zealand housing market have changed some of those factors. Many people are now living in rental accommodation long past their transient years into a time where they have gained permanent employment, formed sound relationships, and have borne children. Based on current trends, there will be a substantial cohort who will live in private-sector rented accommodation for their entire lives.

Therefore we consider that the systems around residential tenancies should be modified to allow for these recent developments.

Many commentators point to various European systems where substantial numbers of people enter into stable long-term rental contracts that allow for security of tenure, certainty of rent levels, and the expression of individuality within the rental property.

Looking at these systems, there are a significant number of deviations from what we consider to be normal and usual under New Zealand laws and our accepted practices. In particular:

- Following WW2, many homes were destroyed and people did not have the funds to rebuild them. Consequently, large organisations and financial institutions rebuilt cities and home ownership fell.

- As many people rented rather than owned their home, laws changed to reflect this situation.

- The organisations providing rental properties own and manage several hundreds if not thousands of such properties and retain that ownership for many years with no expectation of ever selling.

- The Tenants enter into the agreement not only to pay rent on that property but also to be directly liable to pay all other overhead costs of that property such as local authority rates, insurance premiums and utilities.

- When Tenants rent the property they then pay for, supply install and maintain their own floorcoverings, kitchen and bathroom appliances, light fittings and all the other fixtures within the apartment. The property owners then maintain only the exterior of the building with all internal maintenance being the Tenant's responsibility.

- When the tenancy finally does terminate, the rental property must be handed back by the departing Tenant to the property owners in exactly the condition it was in on the day the tenancy commenced. There is no allowance for wear-and-tear.

As can be seen, under these regulations the obligations of the property owners during the term of the tenancy are minimal. This means that these organisations have low operational overheads and can run as viable and sustainable long-term business models.

The NZPIF proposes that a new tenancy option be developed for tenants who want long term tenure security and landlords who are willing to provide it. It would be an additional option to the existing periodic and fixed term tenancies that currently meet the requirements of many landlords and tenants. It provides advantages and disadvantages to both parties.

The tenancy would be available with two options, being furnished and unfurnished.

The furnished version is for tenants that mostly want security of tenure rather than the ability to modify their rental home. The unfurnished version is for tenants who want both security of tenure plus the ability to modify the property and be more likely to have a pet.

The suggested terms of the new tenancy option are:

- Tenancy term negotiable between the parties, but must be for a minimum of three years.

- Tenants may give three months' notice to end the tenancy,

- Landlord can only end the tenancy for tenant default for rent arrears, damage to the property, illegal activity, antisocial behaviour, property uninhabitable or subject to mortgagee sale. (Landlords cannot end the tenancy to move into or sell the property with a requirement for the tenant to vacate.

- If ending a tenancy for antisocial behaviour or disturbing neighbours, landlords must issue a warning notice describing the antisocial behaviour/ neighbour disturbance (without having to name effected neighbours), making it clear that they will end the tenancy if the behaviour/disturbance continues. If the behaviour/disturbance continues, landlords can issue a 90-day notice to end the tenancy.

- Tenants can decorate the property as of right, but must return it to exactly the same state it was provided in, with no allowance for wear-and-tear, unless otherwise agreed to by the Landlord.

- If practical, Tenants can make gardens as of right, but must return it to the state it was provided in at the end of the tenancy, unless agreed to by the Landlord.

- Landlords can charge a bond equivalent to up to twelve weeks rent.

- There is no obligation for the landlord to provide floor coverings, curtains, light fittings or appliances, including stoves. Walls are painted white at the commencement of the tenancy.

- Tenants are responsible for the payment of all insurance premiums, rates, and the costs (both fixed and variable) of services to the property (including water).

- Tenants can only assign their lease with the landlords' consent or on application to the Tenancy Tribunal on grounds of hardship. Hardship provisions also apply to the landlord. Landlords can prohibit tenants subletting the property.

This tenancy will appeal to tenants who want a rental that is more like their own property while providing compensation to landlord's for giving up their ability to terminate the tenancy.

2. Protecting tenants and communities

The law change to improve tenants' security of tenure by removing no stated cause 90-day notices was well intentioned, but misguided. The only available research on these notices showed that they were a tool of last resort, infrequently used and reserved for when no other option is available.

There is no research which shows that the use of 90-day notice was causing problems for tenants. The only research on 90-day notices was a NZPIF survey which showed that 97% of tenants do not receive a ninety-day notice and therefore have not received any increase in their security of tenure from removing their use.

Only 3% of tenants each year received a 90-day notice. Two thirds of these notices are for disruptive and antisocial behaviour. The majority of these notices would be given in order to keep affected neighbours' complaints private and protect them from conflict with the disruptive and antisocial tenants.

Under the current system, it is extremely difficult, time consuming and risky for neighbours to remove a tenant that is behaving antisocially.

-

- The tenant must engage in anti-social behaviour that is more than mild on 3 separate occasions within a 90-day period; and

- on each occasion the landlord must give the tenant written notice describing clearly which specific behaviour was considered to be anti-social and who engaged in it; and

- advise the tenant of the date, approximate time, and location of the behaviour; and

- state how many other notices (if any) the landlord has given the tenant under this paragraph in connection with the same tenancy and the same 90-day period; and

- advises the tenant of the tenant's right to make an application to the Tribunal challenging the notice; and

- The landlord's application to the Tribunal must be made within 28 days after the landlord gave the third notice.

It is up to the landlord to prove that the tenant engaged in the antisocial behaviour and that it was more than mild antisocial behaviour. This means that other tenants or neighbours will probably have to become involved and provide evidence.

Recent Tenancy Tribunal cases have required neighbours of antisocial tenants to appear at the Tribunal to give verbal evidence. Written evidence is not sufficient. This requirement is extremely difficult for affected neighbours and extremely intimidating.

The new laws solution for tenants disruptive and antisocial behaviour is to put affected neighbours at a higher level of risk for a longer period of time. The consequence has been that good tenants depart and bad tenants remain. This is not a good solution.

A BRANZ study shows that 90-day notices are not the main cause of tenants feeling insecure within their tenancies. The study showed that 30% of tenancies are ended because the landlord sells the property. Only 2% are ended from receiving a 90-day notice. Having their home sold is the key reason for a lack of security.

In a study of 2,800 landlords, property managers and tenants by the REINZ found 82.1% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with ending the 90-day notice. Even tenants disagreed with ending the 90-day notice with 45.4% against a change compared to 40.9% supporting the proposed change. A further 13.7% either didn't know or neither agreed/disagreed.

While the NZPIF is very supportive of increasing tenants security, removing the no stated reason clause of the 90-day notice provisions was not the way to achieve it.

The RTA should be changed so that landlords can issue antisocial tenants with a 90-day notice to end the tenancy without having to state a reason why or requiring neighbours to put themselves at risk from the antisocial tenants.

3. Increase maximum bond limit to 12 weeks rent.

In many European countries, there is a recognition that tenant damage and unpaid rent can be extremely expensive for rental property providers.

It often takes 6 to 8 weeks to get a Tenancy Tribunal hearing in New Zealand and then a number of weeks before the tenant actually vacates. In these circumstances a large clean-up is required plus a lot of expensive and time-consuming repairs before the property is fit for a new tenant. The costs of this loss are then often factored into the new rent level set for that property.

The landlord receives a financial and emotional impact when this occurs. To reduce the risk of considerable costs being placed on the landlord, they should be able to charge a higher bond equivalent to 12 weeks rent. On average, this would still represent a security bond of less than 1% of the rental property value.

By reducing the risk of bad tenant behaviour, landlords will be more likely to provide rental accommodation at a lower rental price.

Tenants who conduct themselves well will get their bond back, so such a change will only affect those tenants who abuse the tenancy system.

4. To encourage rental payments, landlords can charge a fee for outstanding rental payments.

By far the most common reason for applications to the Tenancy Tribunal is rent arrears. The majority of landlords understand that tenants will occasionally have unexpected bills and may be late with paying their rent.

However, there are other tenants who are continually late and/or make irregular payment amounts. When the amount increases, tenants often find that they are unable to catch up and their financial situation can spiral out of control.

To establish that paying their rent is an important part of maintaining a stable home and to recompense landlords for the increased time managing these rent payments, it is reasonable that landlords can charge a fee whenever rental payments are missed.

This is similar to banks charging fees on an overdrawn bank account or Utilities and other suppliers charging for unpaid invoices.

The charge would not be automatically applied but at the discretion of the landlord. In this way tenants are not financially disadvantaged by infrequent and unexpected extra costs that may occur.

The rate of the interest charge could be linked to floating mortgage interest rates, which would be appropriate as without rental income, owners would have to fund mortgage payments.

5. To improve tenant's quality of life & minimise rental price increases, make the supply & installation of insulation & energy efficient heating tax deductible.

The NZPIF supports insulation and heating in rental properties as it adds to tenant's quality of life. Like all businesses, the end cost of product or service improvements is ultimately born by the consumer.

As rental property providers cannot claim GST expenses, the Government receives both GST and income tax from businesses supplying these products and services. At the same time, the Government benefits from warmer drier homes through resultant savings in health care expenditure.

The Otago Medical School estimates that the Government saves $5 in health care costs for every $1 spent on insulation and energy efficient heating. By making this spending a revenue rather than capital expense, the Government would still be receiving around $4.72 in health savings for every $1 spent. However, it would be an excellent encouragement for extra spending on insulation and heating and would reduce the requirement for increasing the rental price.

By making these expenses tax deductible, Government would help be make rental properties warmer, drier and cheaper for tenants, improving their quality of life and increasing the stability of their accommodation.

6. Encourage landlords to allow pets:

Many tenants would love to have a pet. Pets make wonderful companions, are often part of the family and help to improve tenant's quality of life. Many tenants would have better, more stable homes if more were able to have pets in their rental properties.

However, some pets can cause considerable damage to properties and/or annoy other tenants or neighbours.

Many landlords would like to allow tenants to have pets, however there is always a risk in doing so. This risk has increased since tenants are no longer responsible for damage that they or their pets cause unless it is intentional.

A further burden is that the Tenancy Tribunal is ruling that if a landlord allows a pet then they have to also expect extra wear and tear on the property. This increases risk and does not encourage landlords to allow pets.

The NZPIF has four suggestions that would greatly encourage more landlords to allow pets in their rental property:

- Tenants responsible for pet damage.

Amend the RTA to reconfirm that tenants are responsible for their pet's damage, just as a home owner is responsible for their pet's damage. - Tenants responsible for problems pets cause neighbours.

Amend the RTA to confirm that tenants are responsible for any problems that their pets cause neighbours, such as incessant barking, just as a home owner is responsible for their pet's behaviour. - If required, pets can be removed without Tenancy Tribunal involvement.

Landlords want to keep their tenants and therefore will be reluctant to end a tenancy because of problems with pets without good reason. Landlords should be trusted that they would only do so as a last resort, first seeking other solutions. If this point is reached, then it should be left to the judgement of the landlord that the tenancy ends (or the tenants choose to remove the pet from the property) without Tenancy Tribunal approval. - Allow pet bonds.

While making tenants responsible for their pet's behaviour is a necessary first step, this does not mean that the financial cost of putting things right will be met by the tenant. In order to reduce the risk of financial loss by allowing pets, landlords should be able to charge a pet bond, separate and additional to the regular bond.

7. Landlords should be able to take out third-party insurance for their tenants, with tenants responsible for the cost.

In addition to reverting tenants to being responsible for any damage they, their guests or pets cause to their rental property, the financial burden should be offset through insurance.

This is because even if responsible for damage, the tenant may not have the funds to cover the cost of repairing the damage. In the event of a fire or some other large incident it is very unlikely that the tenant will be able to afford the repairs, with no guarantee that the landlord's insurer will cover the costs

To ensure that both the tenant and the landlord are protected, it is desirable that the tenant has contents insurance or at least third-party insurance.

While a tenant could take out this type of cover to obtain a rental property, there is nothing to stop them cancelling the policy once they move in. For this reason, the policy should be taken out by the landlord but with a requirement that the tenant is responsible for the cost, just like utility payments such as water or electricity.

8. Help tenants with bonds

Tenants can find it financially difficult when moving between tenancies. Existing landlords do not want to release the bond before the tenant has moved from the property and a final inspection has been completed. New landlords want to collect a bond on signing the tenancy agreement in case the tenant breaks the agreement before the tenancy starts.

It would help tenants moving into new tenancies by processing undisputed bond refunds within 5 days, to reduce the time that they are likely to cover two bonds for their existing and new tenancy.

It would further help if the Government guaranteed the bond to the new landlord from the time the tenancy agreement is signed up until the tenant has their existing bond repaid and is able to transfer it to the new landlord.

Lower Costs, Lower Rents

Like everything, if costs increase then the price for the end consumer increases. This is the same for rental properties.

Over the last 8 to 10 years, many of the costs in providing a rental property have increased. This includes rates, insurance, repairs, maintenance and tax. In addition, new tenancy laws have made it more difficult and expensive to manage rental property, plus rental property standards have increased adding to the cost of rental property.

It is fortunate that mortgage interest rates have reduced and have somewhat offset these other cost increases. However, it is predicted that mortgage interest rates are likely to increase over the next few years, thereby removing any ameliorating affect their previous reductions may have provided.

The NZPIF supports laws that improve tenant's standard of living. However, it must be a genuine and desired improvement for the tenant, introduced in a cost-effective manner as it is the tenant who will ultimately pay for the improvements.

Some changes to rental property over the last few years have not been developed for the benefit of tenants. These changes have actively sought to disincentivise the provision of rental property in an attempt to reduce competition for First Home Buyers. Unfortunately, this has led to rental prices being higher than they should be and reducing the supply of rental property, leading to the highest number of people on the social housing waiting list and $1,000,000 of taxpayer funds being spent every day on emergency housing.

It appears that there is a political objective to reduce the private sector supply of rental property and encourage social housing providers and corporate rental providers. Both these providers are more expensive than existing private rental providers, which is mainly made of small property owners taking a long-term perspective of providing rental property and undertaking many of the management and maintenance tasks themselves.

The NZPIF believes that small scale private providers of rental property are better for tenants and tax payers, as they provide good housing at reasonable prices requiring tenants to have lower requirements for state assistance with their accommodation.

The following are proposals to reduce unnecessary costs in the provision of rental property and reduce pressure on rental prices to increase more than they need to.

1. Return mortgage interest costs to be a tax-deductible expense.

Mortgage interest payments can be the highest cost in providing a rental property. Residential renting has been defined by MBIE as a business. Borrowing to run a business or make an investment has always been considered a tax-deductible expense, including for rental property. It is not a tax loophole as it has been asserted.

Rental property owners do not have a tax advantage over home owners because they could previously deduct the mortgage interest as a tax deduction. While rental providers pay tax on the rental income they receive, home owners do not pay any tax on the value of the accommodation they receive.

There is no benefit to tenants in making rental property debt non-deductible. It does not improve the standard of their rental property and it does not improve the terms of their tenancy agreement. The only thing it can do, as confirmed by multiple Government Policy Advisors and Economists, is increase rental prices.

Policy advisors at the IRD, Treasury and Ministry of Housing all advised Government not to introduce this policy. There has been no research undertaken on the likely affect this policy will have.

A letter signed by the NZPIF, Tenants Protection Association and even the First Home Buyers Club advised the pitfalls of the policy and asked that it not be introduced. This request was declined. It is quite a damming situation when representatives of the people that a law change is designed to benefit, First Home Buyers, do not want it to proceed.

The NZPIF is the only organisation that has undertaken any research on the proposed tax law change. In a survey of 1,719 rental property providers, just over 90% would be affected by having to pay extra tax on their rental property.

The average increase in tax from removing mortgage interest deductibility was $15,083 per affected rental provider and $3,140 per rental property.

If this figure is representative of the total rental property-owning population, then the cost of the extra tax could be $1.5 billion.

To cope with this tax increase, the majority of respondents, 76.8%, will either "increase" or "probably increase" rental prices. A further 8.9% "might increase" rental prices.

Approximately 21% of respondents would consider selling either some or all of their rental properties. About half of these would sell all of their rentals, with the other half considering selling an average of 2.45 rentals or 34% of their portfolios.

It appears from these results that the Government's new tax laws will affect a large majority of rental property owners, increasing costs by around $3,000 per rental property. Respondents' primary response will be to increase rental prices which seems feasible given that 70% are currently below market levels.

The NZPIF believes that only the United Kingdom has introduced any tax change similar to this. Unlike NZ which will completely remove interest deductibility for rental property over four years, the UK will merely reduce the percentage rate that rental providers can claim. Because of this, UK law makers believe only 15% of UK rental providers will be affected, unlike the 90% of NZ rental providers.

This tax change will have an enormous effect on the cost of providing rental property and property and inevitably push up rental prices. The tax change should be withdrawn or at least introduced in a similar way to the UK.

2. Repeal ringfencing to increase the supply of rental properties for tenants.

The Taxation (Annual Rates for 2019–20, GST Offshore Supplier Registration, and Remedial Matters) Bill was introduced in June 2019. This included ringfencing of tax losses on rental property, meaning that any losses incurred from this activity could not be used to offset tax paid on other income. This offset is a tax allowance available to all other businesses and investments.

Instead, rental property losses are "ring fenced" until the property is making taxable profits, when the tax losses can then be applied to the rental profits.

The stated purpose of ring-fencing rental losses was to "level the playing field" between property speculators/investors and home buyers. It was believed that there was unfairness in the system because investors (particularly highly-geared investors) have part of the cost of servicing their mortgages benefitted by the reduced tax on their other income sources, helping them to outbid owner-occupiers for properties. Ring-fencing rules were intended to reduce this perceived advantage and diminish the attractiveness of providing rental properties for tenants.

A report by independent economic consultants, Morgan Wallace, states that "our analysis does not establish any bias in the after-tax returns available to an individual entering the property market either as an investor, homeowner or tenant. To that end the housing market can be considered a "level playing field".

The Morgan Wallace report establishes that the entire reason for the law change was flawed.

While some rental property providers have had to sell rental property because they can no longer afford to keep them, the greatest effect has been to make it harder to provide new or replacement rental property.

In New Zealand, rental prices in relation to incomes and house prices are low. Lower rental prices and high costs to provide rental property mean that in many instances rental properties make losses in the initial years of ownership. Before ring fencing was introduced, rental property owners could reduce the full impact of these losses by using them to offset the tax liability on other forms of income.

A 2019 NZPIF study shows that the cost of buying and providing the average NZ property as a rental is $9,951 in the first year. When this loss was able to be used to reduce other taxable income, the cashflow cost was reduce to $5,908 in the first year. With the new ring-fencing laws in place, rental property providers must meet the full loss of $9,851, making it considerably harder to fund the rental property.

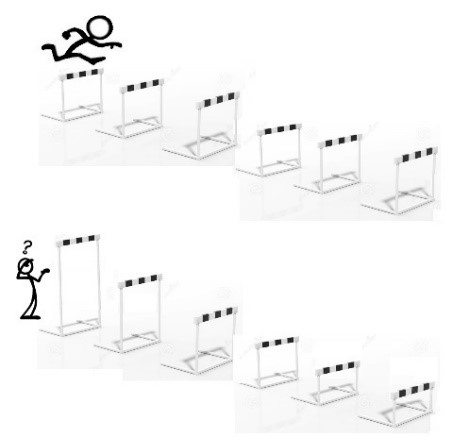

The following illustration portrays the effect of ring fencing on the cashflow position of rental property providers. Before ring fencing, tax laws evened out cashflows by reducing the impact of losses in the early years and imposing tax payments in subsequent years when the property was profitable. With ring fencing, rental property owners wear the full cost of losses in the early years and then receive the deferred tax deductions when the property is making profits.

Many potential rental property providers simply cannot get over that first negative cashflow hurdle and are therefore prevented from providing a rental property. This has reduced the supply of rental properties at a time when we need many more.

Ring-fencing does not provide any additional tax revenue to the country, it merely defers it into future tax years. Ring-fencing does not provide any benefits to tenants, it can only serve to decrease supply and increase rental prices. Ring-fencing does not provide any benefits to first home buyers as they were never adversely affected by it in the first place.

Ring-fencing has a dramatic effect on large and costly repairs, such as reroofing or painting the property. These large and one-off costs can put a cashflow positive rental property into a loss-making situation during one financial year without the ability to use the loss in the same year. This is encouraging ad hoc and piecemeal repairs and maintenance.

In order to maintain rental property supply and minimise rental price increases, the ring-fencing rule needs to be repealed.

3. Rental property owners are not speculators. To encourage more rental properties, return the Brightline Test to 2 years.

The Bright Line Test was introduced by the National Government in 2015. As with other asset classes, any profit made from property that was bought with the intention of resale is taxable as income tax. Any increase in value from an asset bought for the income it provides is not taxable.

The National Government believed that the "intention test" was too subjective and that people whose real intention was to sell a property at a profit were pretending to be a rental property provider and avoiding their responsibility to pay tax.

While this was a reasonable concern, the Inland Revenue Department established the highly successful Property Compliance Division to address this situation. The IRD was able to investigate and prosecute people trying to pass themselves off as rental property providers and avoid paying income tax on profits they made from trading properties.

Despite the success of this IRD Division, there was a public perception that most property investors, including rental property providers, were avoiding paying tax they should pay.

The Brightline Test assumed that anyone who sold an investment property within two years was really a property trader and should pay tax on any increase in value. While aimed at property traders and speculators, the Brightline Test affected rental property providers as well.

The Labour Government extended the Brightline Test to five years, which had no effect on real and actual property traders or speculators, only on rental property providers.

Despite this, the Labour Government extended the Brightline Test again to five years making the test a pseudo or partial Capital Gains Tax, one solely applied to residential rental property.

This is a disincentive for people to provide rental property and has reduced the potential supply of rentals for tenants while also increasing rental prices.

The Bright Line Test should be returned to two years thus increasing the supply of rental property and minimise pressure on rental prices to rise.

4. Tax the income from rental property at 10.5%.

If Government wants to reduce rental prices for tenants and make it easier for them to save a deposit for a home of their own, then they should lower the rental property tax rate.

As higher tax increases the cost of goods and services, lower taxes reduce costs and decrease the requirement for higher prices.

As many tenants are low-income earners, it makes sense that their rental costs are taxed at the lowest income tax bracket.

5. Make Accommodation Supplement equal to Income Related Rents

The current waiting list for state housing is currently over 23,000. The state house waiting list was over 12,000 in 1972, and while it is higher now, this shows that there has always been a shortage of state housing.

A contributing factor to the state house waiting list is that the Income Related Rent policy for the State and registered social housing tenants Is more generous than the accommodation supplement available to tenants renting in the private sector.

The tenants on the state house waiting list, currently renting from the private sector, should not be disadvantaged because of the landlord they have.

A more equitable system would be to better align the Accommodation Supplement with the Income Related Rent policy. This would benefit low-income tenants renting in the private sector while reducing the incentive to want a state house and thereby reducing the state house waiting list.

6. Tenants should be responsible for damage.

The Osaki case High Court ruling meant that tenants were no longer responsible for any damage that they or their invited guests caused to their rental property. This was because the Osaki's, who almost completely destroyed their rental property, didn't have contents insurance to cover them for the damage they accidently caused. The insurance company was pursuing them and the High Court Judge did not believe this was far.

However, the ruling meant that tenants were no longer responsible for ANY damage that they caused to their rental. It was generally accepted by all Political Parties that this was an impractical and undesirable situation, totally unfair to rental property owners.

It took a considerable length of time for the National Government of the day to address the situation. The Minister in charge at the time considered Insurance companies were double dipping through a rental property being insured by the owner and also by the tenant through their content's insurance.

Unfortunately, this was a misunderstanding. The owner protected the property through their property insurance policy, which did not cover damage caused by the tenant. The tenant could protect themselves through their contents insurance policy, which provides third party liability cover which covers a multitude of situations, including damage the tenant may do to their rental.

The owners house insurance policy was relatively cheaper because it did not cover the tenant. The tenant could only protect their belongings plus any liability they were responsible for, including the rental property by holding a contents insurance policy. This means that insurance companies were not receiving insurance premiums from both owners and tenants covering the same risk of damage.

If the tenant was responsible and did not make a high number of claims on their content's insurance, then their premiums would be lower than other tenants who were less responsible and made a lot of claims. This situation would ensure that responsible tenants receive a benefit from their good actions through lower insurance costs. It would also mean that the tenant could take their contents policy with them when they moved to a new rental.

Currently we have a partial and complicated resolution to the problems caused by the Osaki High Court ruling.

Tenants are still not responsible for damage they cause, but could use their landlord's insurance policy for the damage but only having to pay either the excess or four weeks of rent, whichever was lower.

This introduced complications. Tenants' responsibilities were determined by the rent they paid or the landlord's excess level, not their own level of culpability. Because they didn't take out the insurance policy, Tenants are unaware of what they are covered for and what the excess is.

To counter this, rental property owners are now required to inform the tenant of their insurance policy and what the excess is, plus any changes to the policy over time. This statement must be made in the tenancy agreement and owners are fined if they do not.

Landlords insurance is now more expensive because it covers tenants as well. Landlords now have to make a claim for damage that their tenants caused, then attempt to get the excess back from the tenant if it was intentional damage.

The RTA says that tenants causing careless damage must pay the landlords excess, but is silent on accidental damage. When going through due process, the NZPIF was informed by policy advisors that the RTA does not differentiate between careless and accidental damage, therefore tenants would be liable to pay the landlords excess for any accidental damage as well as careless damage they caused.

Unfortunately, the Tenancy Tribunal has determined that accidental damage is not covered by the Act and therefore tenants who accidentally damage the rental property not only get to use their landlord's insurance policy but the landlord is responsible for paying their excess. It is demonstrably unfair for an uninvolved landlord to have to pay their tenant's excess.

Tenants who have contents insurance receive no benefit from this new ruling, as it only benefits tenants without contents insurance. Tenants with contents insurance actually pay twice. Once for the policy and again through higher rental prices because of the landlord's higher insurance costs.

In addition, the new Act entices tenants not to take out content's insurance, not realising that it covers them for much more than just damage to their rental property.

Tenants are responsible for each incident of damage and therefore the excess that insurance companies charge for each incident. Rental property excesses tend to be high, so this exposes tenants to potentially very high costs through multiple incidents of damage.

The NZPIF recommends that the current situation is repealed and we revert to a solution that is easier for tenants to understand, provides better protection for tenants, reduces the need for higher rental prices and doesn't increase costs for tenants that already have contents insurance.

Our solution is to return Tenants to being responsible for damage they or their guests cause, and for a requirement for landlords to advise tenants of their risk and that they can protect themselves by taking out contents insurance. In this way, tenants can make an informed choice about whether they want to take out the insurance.

This will reduce costs for landlords and remove uncertainty for tenants.

7. Government provided low interest mortgages

Mortgage interest is a significant expense for many rental property providers. When interest rates are low, then there is less of a requirement to raise rental prices.

To encourage lower rental prices and more stable tenancies, rental providers offering long term tenancies could be provided mortgage funds at lower interest rates that can be obtained from Government sources.

More rental properties

While there is considerable media attention towards a shortage of housing for first home buyers and social housing tenants, very little is said about the shortage of rental property for regular tenants. Private landlords need to be recognised and encouraged to provide homes for these tenants.

Private rental providers currently supply around 85% of rental accommodation in New Zealand. There is a campaign to reduce the number of small scale private rental providers and replace them with Build-to-rent Developers, institutional investors and Community Housing Providers (CHiPs)

Small scale rental providers supply good properties to tenants, are not so focused on obtaining high short term cashflow and have significantly lower operating expenses and overheads. For these reasons small scale rental providers are the best providers of good quality properties at reasonable rental prices that do not require as much support from tax payer funds.

The only current advantage that other rental property suppliers have over existing small scale private rental providers is security of tenure. However, this could be easily solved by introducing the Long-Term Tenancy option proposed by the NZPIF and based on the German tenancy model.

In order to solve the rental crisis, without larger requirements for Government funds, we need to encourage more investment from small scale rental property providers.

Many of the previously mentioned NZPIF proposals will also encourage the provision of more rental properties. The following are additional solutions to encourage the supply of more rental properties.

1. Tenancies extended at the end of a fixed term must be under the same terms and conditions, not automatically periodic.

It is completely unfair that one party to an agreement has a higher level of rights than the other. However, this is how fixed term tenancies are now currently structured, which is putting people off providing rental properties.

Previously fixed term tenancies had an end date and if either the tenant or the landlord didn't want the tenancy to continue then the tenancy would end. With new rules, if the landlord doesn't

want the tenancy to end but the tenant does, then the tenancy must continue as a periodic tenancy. This is completely unfair.

There are two options to rectify this situation and encourage the provision of more rental properties. The preferred option is to revert fixed terms tenancies back to how they were, where both parties had to agree to the tenancy continuing after the date that the fixed term ended.

This is the preferred option as it is fair to both parties and provides more certainty. It is especially difficult for managing student tenants, as these properties are often relet before the end of the academic year as this is easier for student tenants to view the property and secure accommodation without having to cut short their academic break to find accommodation for the new academic year.

An alternative solution is that if the tenant is to have a higher say than the landlord, then the tenancy should not automatically revert to a periodic but should continue on the same terms and conditions as before.

1. Retain a landlord's right to charge a fair market rental price.

As extra costs, higher taxes and tougher tenancy laws have seen rental prices increase more than otherwise would have, there have been calls from some tenant advocates for rent controls.

There are few places in the world that have rent controls and the vast majority of experts and economists agree that there are serious flaws with rent controls.

Rent controls put people off providing rental properties and therefore restrict supply. As New Zealand has a shortage of rental properties, rent controls would only make the matter worse.

In reality, rental prices are already controlled in that they cannot be changed within one year of them being set. In addition, rent increases are restricted to being no more than current market rates, with tenants able to have a rent increased reversed by the Tenancy Tribunal if it is deemed above market rates.

Government have so far stated that additional rent controls do not work and are not being considered. However, there is still considerable lobbying for them to be introduced. Rental prices should not

be the only product or service in the free market that are subject to additional price control.

We would encourage Government to resist acting on these calls to introduce rent controls and look to reversing decisions that actually led to rental price increases in the first place.

This is continued in Fixing the Rental Crisis - Part 2. Putting things right.